On February 2, the Church celebrates the Presentation of the Lord, also known as the Purification of Mary, in which Scripture and Tradition meet at several points. Forty days after Christmas, the arc of Jesus’ life that we trace through the liturgical year continues with his first visit to the Temple, required by Jewish custom forty days after a child’s birth. There, Jesus meets two elderly prophets, Simeon and Anna, as described in Luke 2:22-40.

Alongside this threshold moment in the lives of the mother and child stands the theme of light in the darkness. As Simeon greets Jesus at the Temple, he names the baby “a light for revelation to the Gentiles.” At the same time, this feast falls halfway between the solstice and the equinox, which is the point in the year when, in Northern Europe and North America, the lengthening of daylight first becomes perceptible. So the groundhog and other customs related to spring forecasting1 build on this theme of the return of light to the natural world, whereas in the Church, the candles are blessed, which gives this feast its more familiar name — Candlemas.

But for me, the central meaning of this feast is captured most clearly in yet another name for it, which exists in Slavic languages. There, Candlemas is called Sretenije — the Meeting — derived from Old Church Slavonic stretenije, a noun formed from the verb stretiti, meaning “to encounter” or “to come upon.” Its modern Russian equivalents are vstretit’ (to meet) and vstrecha (a meeting), with cognates in other Slavic languages (e.g., Bulgarian среща and Serbo-Croatian сусрет), all stemming from the same Proto-Slavic root denoting a mutual arrival or intersection.

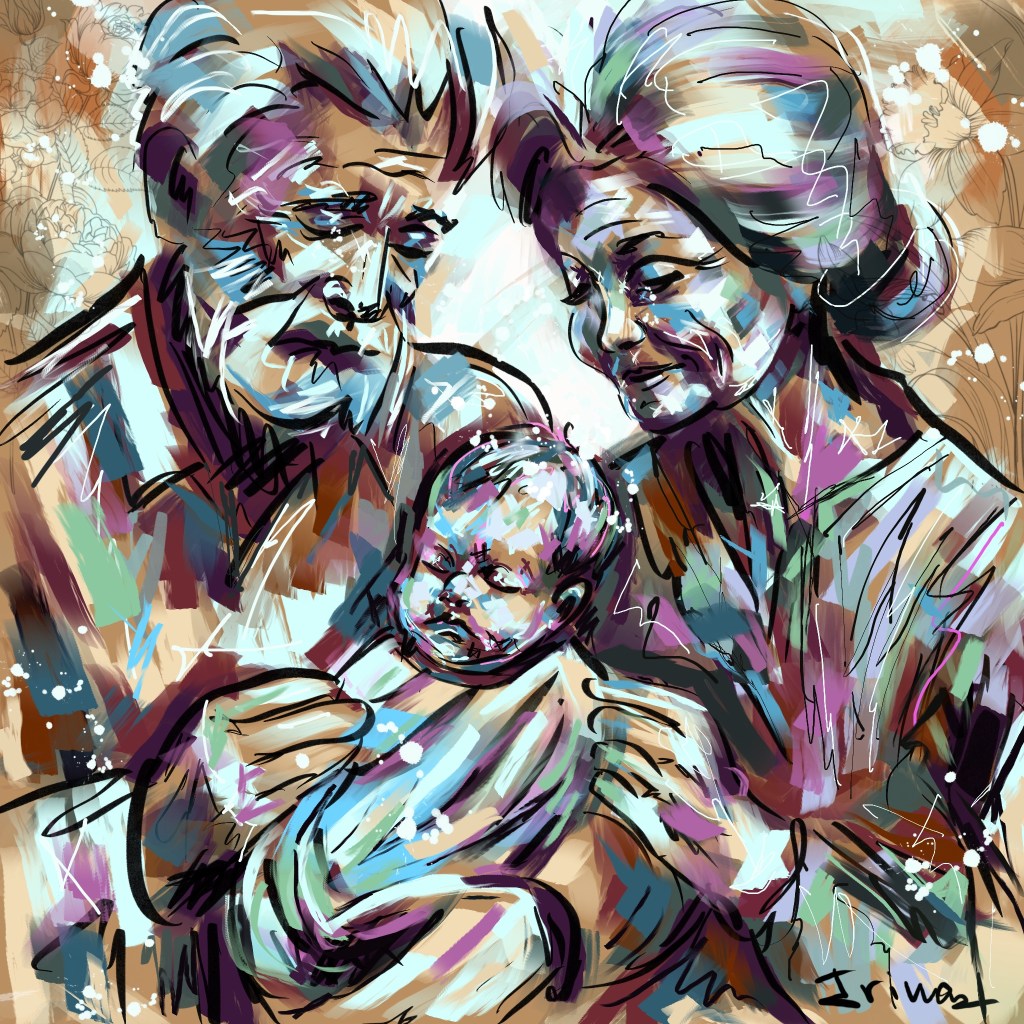

This is not the language of seeing or observing, but of coming face to face, of receiving and being received: two parties move toward one another, and something is changed by that encounter. And that, I think, is the heart of this feast. It is not only about what happens to Jesus and Mary, or to Simeon and Anna, but about what happens between generations — between hope and experience, between those just beginning life and those nearing its end. And that makes it a feast with particular resonance for a community like ours, rich in grandparents and elders who find themselves meeting Christ again in the young.

The Gospel story itself, however, is strikingly unsentimental:

When the time came for their purification according to the law of Moses, they brought him up to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord (as it is written in the law of the Lord, “Every firstborn male shall be designated as holy to the Lord”), and they offered a sacrifice according to what is stated in the law of the Lord, “a pair of turtledoves or two young pigeons.” (Luke 2:22-24)

Forty days after Jesus’ birth, Mary and Joseph make the journey from Bethlehem to Jerusalem so that Jesus may be literally bought out of the role assigned to all firstborn sons, as those offered to God for priestly service. This custom reaches back to the Exodus, when the firstborn sons of Israel, spared through the blood of sacrificial lambs — unlike their Egyptian counterparts — were effectively claimed by God as those who belonged to him. This lasted until the establishment of the priesthood of the tribe of Levi, chosen after the incident of the Golden Calf, when the Levites alone remained faithful to YHWH.

Yet long after the Levites replaced all firstborn sons as priests, the ritual endured. And as another highly symbolic moment in Jesus’ story (within Matthew’s chronology), shortly after the return from the Temple, the Holy Family would receive the Magi and flee back toward the land to which Mary’s ancestors had once gone to escape famine, and from which they had later escaped slavery on Passover night.

At the time of this Temple visit, however, all of this lay hidden. What must have preoccupied Mary most was simply recovering, caring for a newborn, and emerging from six weeks of enforced isolation — perhaps wise for infection prevention, but psychologically taxing. Like all first-time parents, she was exhausted, sleep-deprived, and emotional. Joseph’s Bethlehem relatives might still have “had no room” for an unwed couple, though a few of the nosier ones may have turned up for Jesus’ circumcision, brit milah, on the eighth day. Now it was time for the next rite dictated by tradition — more scrutiny, and more travelling. Ten kilometres is a long walk with a six-week-old child, especially in the heat!

Joseph, too, was displaced — away from his tools, his clients, his livelihood — acutely aware of how limited his resources were. The sacrifice they brought, two doves, is explicitly identified in Scripture as the offering of the poor. Perhaps this was the first time he felt how close his young family stood to the edge of poverty, and all that such vulnerability does to one’s sense of dignity and responsibility.

It is important not to rush past this. This is not a glowing, serene moment. Like most aspects of Jesus’ infancy, it is shaped by fatigue, vulnerability, and necessity. And yet it is precisely here that God was encountered.

Likewise, the Temple was a place where blood, struggle, prayer, commerce, longing, hope, and belonging converged. Mary and Joseph saw it all: the pool where sacrificial animals were washed; the courts where merchants sold innocent animal lives so that those who bought them would go free. Their own small bag fluttered with the two helpless birds soon to be killed. Of course, Mary had no way yet to grasp how deeply these themes would one day shape the meaning of her son’s life and death — still less that countless people would come to believe that the baby she brought to be redeemed from a priestly role would himself become the High Priest, forever binding God and humanity, both in his own body and in the Body of the Church.

And then, out of the crowd, two elderly figures stepped forward:

Now there was a man in Jerusalem whose name was Simeon; this man was righteous and devout, looking forward to the consolation of Israel, and the Holy Spirit rested on him. It had been revealed to him by the Holy Spirit that he would not see death before he had seen the Lord’s Messiah. Guided by the Spirit, Simeon came into the temple, and when the parents brought in the child Jesus to do for him what was customary under the law, Simeon took him in his arms and praised God, saying, “Master, now you are dismissing your servant in peace, according to your word, for my eyes have seen your salvation, which you have prepared in the presence of all peoples, a light for revelation to the gentiles and for glory to your people Israel.” And the child’s father and mother were amazed at what was being said about him. (Luke 2:25-33)

Simeon and Anna were neither priests in positions of power nor authorities issuing judgments. They were elders who had been waiting long enough to have learned patience and attentiveness. I wonder whether the moment itself unsettled Mary, as any parent knows the instinctive tightening that comes when a stranger reaches for their baby. Nonetheless, she let Simeon hold the child and heard the words that the Church has prayed every night for centuries: “Lord, now you are letting your servant depart in peace.” It is an astonishing reversal. An old man speaks of dying in peace because he is holding a six-week-old infant. His hope for the end of his life is fulfilled not through personal achievement or rational explanation, but through his recognition of the presence of God in this child. He speaks of salvation, light, and resurrection. (Luke uses here the same Greek word for “rising” or “standing up again” that he will later use for resurrection itself.)

But then came the harder words:

Then Simeon blessed them and said to his mother Mary, “This child is destined for the falling and the rising of many in Israel and to be a sign that will be opposed so that the inner thoughts of many will be revealed–and a sword will pierce your own soul, too.” (Luke 2: 34-35)

Any parent and grandparent understand what it means that “a sword will pierce” Mary’s soul. To love is to risk grief, and to watch a child grow is to know joy and loss, pride and fear. Most caregivers have moments when they “lose” a curious child in a store or in a park; or even in this very Temple, where Mary once found Jesus after frantically searching for him at the age of twelve. Behind all such moments lies the fear no parent wants to name: not merely losing track of a child, but losing them before one’s own life ends. Yet Simeon blessed Mary even as he named the cost.

Anna, too, stepped forward — an elderly woman who had spent decades as a widow in prayer and devotion:

There was also a prophet, Anna the daughter of Phanuel, of the tribe of Asher. She was of a great age, having lived with her husband seven years after her marriage, then as a widow to the age of eighty-four. She never left the temple but worshiped there with fasting and prayer night and day. At that moment she came and began to praise God and to speak about the child to all who were looking for the redemption of Jerusalem. (Luke 2:36-38)

The poem “Anna the Prophetess” gives voice to this moment, as she remembers her youth. Then the sun rose for her, and life felt full of promise; now she is old, poor, overlooked, crying in the dark. But when Anna held the infant, in the weight of his small body and the meeting of their eyes, she remembered every hope stored in her childhood’s heart. In this small instance of resurrection, Anna recognized the holiness of the body itself — the dignity of life at its beginning and at its end.

This is the Meeting. It does not erase loss, but as the very old meet the very young, God is revealed. It is always those on the margins who are most ready to encounter Jesus: shepherds in a cave, elderly people in the Temple, fishermen by the sea, women at the empty tomb. And the irony of this feast is that the sacrifices offered that day did not spare Jesus from becoming, paradoxically, both high priest and sacrificial lamb. Mary, far from merely becoming ritually clean, would come to be regarded as the holiest of women. None of this could have been foreseen at the time; that theological vision would take decades, if not centuries, to emerge. Only Simeon and Anna, given their prophetic insight, expected something of this child that went beyond the cultural or logistical expectations placed on young people in every society. They trusted that God would bring about a reality through this child beyond what they could fully name.

What expectations do we have of ourselves? What have others expected of us? May each of us one day realize that God accomplishes infinitely more in us than anyone, including ourselves, could ever ask or imagine. We all know how fragile life is, how little we can control, and how meaning takes time to arrive. But in a grandchild’s curiosity, in a child’s question, in the presence of younger people in this community, we meet Christ again and again — not as an idea, but as a Presence. We might not understand it fully, but let’s hold it for a moment, bless it, and let it go in peace. May this feast teach us how to meet Christ in one another, and most of all, in ourselves, and to see these meetings as gifts.

- “If Candlemas Day be fair and bright,

Winter will have another flight;

If Candlemas brings cloud and rain,

Winter won’t come again.”

↩︎

Questions to Consider

- In Slavic languages, the feast’s traditional name Sretenije means “the Meeting.” Where in your own life recently have you felt you met God — perhaps not in words, but in presence, in another person, or in a moment of prayer?

- Candlemas comes at a turning point between winter and spring, and also half-way between the Winter Solstice and Spring Equinox. How do you see signs of light and hope in your life right now? Do you feel the “winter” of something difficult is giving way? Or are you still in the midst of it?

- Many traditions, including Groundhog Day and old Candlemas weather proverbs, explore how we look for signs of change in the world around us. How do you balance looking for signs of hope externally (in the world) and internally (in your own experience of faith)?

- Who in your life — young or old — helps you recognize Christ? How might God be inviting you to meet Christ in someone unexpected this week?

- Spend a moment in silence, then pray for the young ones in your life and for the elders you know. Name aloud or in your heart one specific way you hope to grow in meeting Christ through them.

Leave a Reply