We’ve had some opportunities recently to appreciate the extent of our parish activity, and thank those who give of their time and effort. Another thing worth remembering is that everything we offer here is fully dependent on your financial generosity. Staff and stuff, activities and music, food and coffee, electricity and communion – it’s all because of you! The Diocese does not fund us; in fact, we pay a tax to fund all diocesan work, including the grants for which we sometimes qualify. Today, you receive an attractive brochure that does a great job of bringing to life all the complexity of our accounting that, when presented in purely numerical form, frankly tends to be a bit boring.

So I hope that this visual and narrative representation of our parish life might inspire you to celebrate, continue or even reimagine your support, and I’ll also share my personal theology of stewardship. To me, it distills to just one concept: hospitality. Welcoming friends and strangers, mourners and those who celebrate, needy and those who share our enjoyment of God’s gifts. And since in all the work that we do with people, we also welcome the presence of God, to me, hospitality is not at all peripheral to our “serious” business of prayer, worship, and learning; nor is it redundant to me to invite the presence of the omni-present God. Two reasons for this.

First, Germanic/Romance “welcome” is quite different from the Greek “dechomai” in Jesus’ phrase, “whoever welcomes me, welcomes the one who sent me”, and Paul’s, “ welcome one another, as Christ welcomed you”. Our “welcome” means “it is good you have come”, like the French “bienvenu” and Spanish “bienvenidos”; Old Norse “velkominn” and Old English “wilcumian”; modern German “das Willkommen” and etc. But “dechomai” is mainly to “receive”– plus, a whole lot more: to grant access; not to reject or refuse; educate and learn; receive favourably; listen; embrace; make one’s own, sustain, bear, endure… Based on this, hospitality becomes neither redundant or superfluous to church, but rather all-encompassing! Even if it is not “well” that someone came, or if we don’t particularly like or love them.

Thus, to receive is a conscious choice. The Bible overflows with examples of such choices. Consider just one: Abraham’s three visitors. They arrived unbidden, and stood beside his tent – a BC equivalent of ringing the doorbell! Abraham was sort of free to invite them; but then again, he was not, since in his part of the world, hospitality is a matter of duty – then, in 2000 BC, or in the 1st century AD, or now. In such an arid land, the survival of anyone, king or slave equally, depended on finding and sharing water. It was also normal for the messengers/servants to receive the same hospitality as their “bosses”, hence Abraham’s lavish treatment of those whom he received as the messengers of God. The 3 measures of flour (i.e. 24 L), plus meat and yogurt, to feed only them, while our Christmas Kitchen uses 120 L to supply tourtière to all of North Toronto!

A few times, Jesus similarly provided overabundant wine and bread; but, in most stories, he is a guest. So on a related note, the text has Abraham addressing his three guests sometimes in the singular form as well, hinting that they weren’t only the messengers of, but God himself (the Holy Trinity portrayed by Rublev!). As such, Abraham’s hospitality remains a universal symbol of the human response to God – but notice that the vehicle for the arrival of God’s presence is, again, the human form. In the gospels, God reappears as a human to eat and drink, and rely on people’s invitations and hospitality. And to teach us to love both God and neighbour, because every time we welcome a neighbour, we come in contact with God. That’s my second reason why hospitality isn’t optional in the church.

But hospitality entails vulnerability for both hosts and guests: would we and our possessions remain safe and respected? Jesus’ “dechomai” in Matthew follows the warning regarding the costs of following him. The greatest cost, I believe, is change. The early church learned this fast, and became primarily ex-pagan, rather than ex-Jewish (in terms of the background of most if its members) within only a few decades of receiving the Spirit. Today, when we take communion, we receive the body and blood of Jesus – and consequently, if we together make up his body, then we receive one another, and all our differences. So today, would you consider trying to welcome God and others in some new, non-intuitive ways? A “busy” person might try meditation. An intellectual – listening. A shy person – greeting, or reading. A prayerful person – giving money or time. And so on. In doing so, may we, like Abraham, embrace an openness to newness and change, and expand the breadth of hospitality already present in our parish. Amen.

Questions

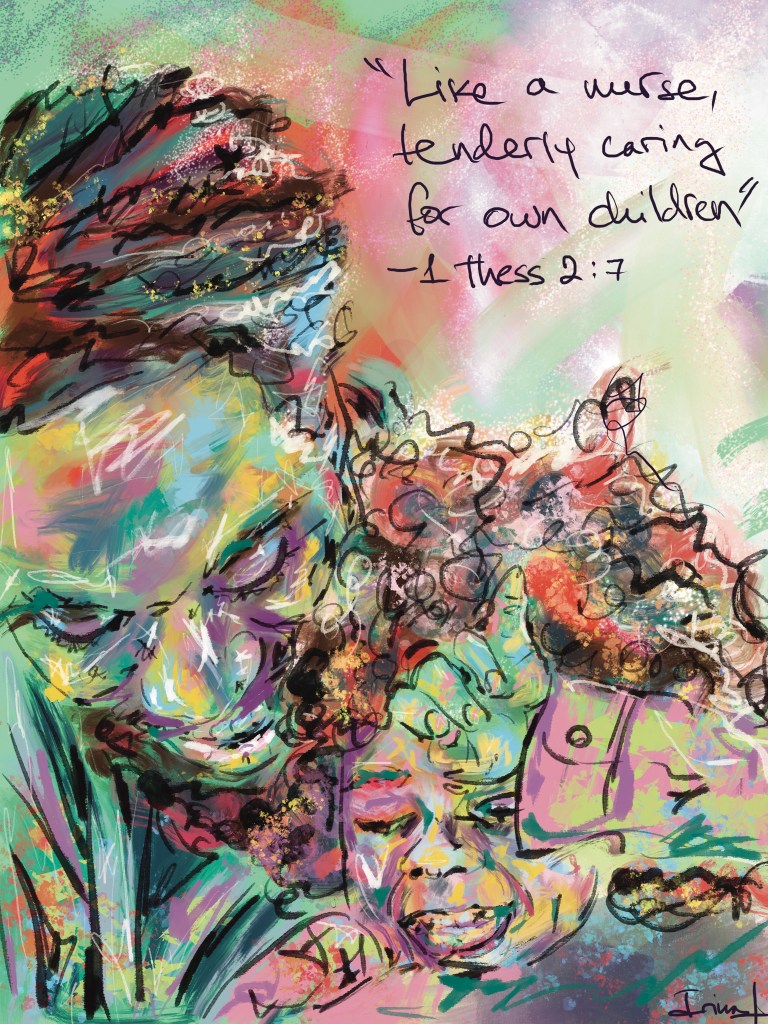

1. Let us ponder the images of compassion that hold personal meaning for us – given and received. (Which ones, do you think, would be easier to recall?)

a) For me, some of the most memorable experiences as a “giver” come from my ministry: bringing the last rites and conducting the funerals, offering prayers and compassionate listening; and also, contributing to the joy found in marriages and baptisms, and shared insights that emerge from studying God’s truths together. It feels good to give, in sadness and in joy. I wonder, however, why these examples came to my mind more readily than those from my family life. What about you?

b) Are we also open to receive the gifts offered to us by others, humbly and gratefully, and admit our reliance on the hospitality of others? What are some of your most memorable big and small instances of compassion extended to you?

2. Recalling some familiar biblical examples of hospitality, consider which one reminds you the most of yourself: are you like Martha, Mary, Abraham… Many miracles of Jesus (e.g., the healing and feeding of multitudes, rescuing the disciples in a storm, ect.), may also be read as examples of compassionate hospitality that was integral to his society. In your own relationships with God and people, do you lean towards being contemplative or active? Listening or doing? Giving financially or in kind, or of your time? How can we better recognize our value to God in spite – indeed because! – of these differences?

3. As a community, how may we best balance our strengths and weaknesses, natural inclinations and personality differences? What would you personally do to help us counter the proverbial “sword” (“I came to bring not peace, but a sword”) with hospitality, freely offered as well as readily appreciated?

Leave a Reply to Mary Pember Cancel reply