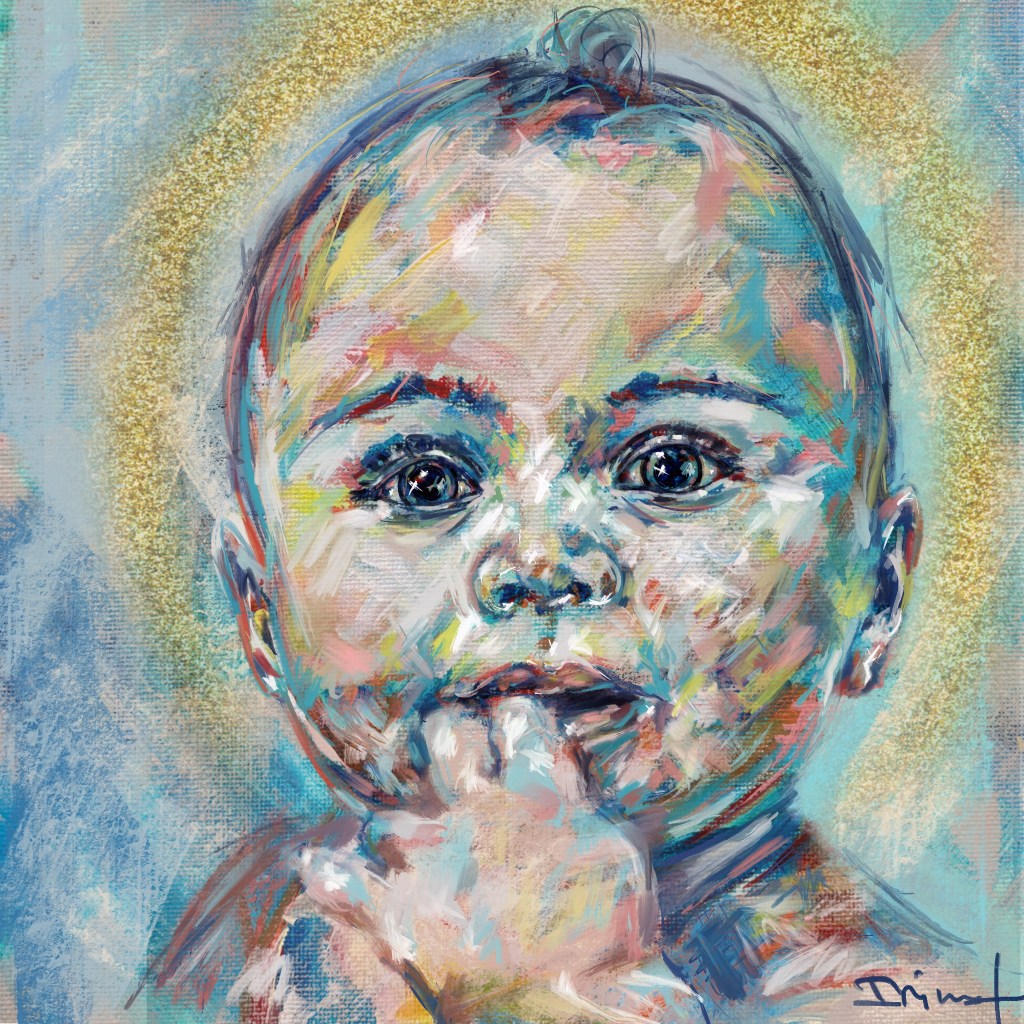

This portrait—begun in acrylic on canvas and completed digitally—is of my youngest child, whose recent questions about God, miracles, and imagination shape much of this reflection. She embodies a kind of wonder unburdened by adult scepticism or by any shyness about seeming infantile in asking questions. I wanted the image to remain unfinished, layered, and luminous: a small visual meditation on incarnation, becoming, and the holy work of asking good questions.

Christmas, at its heart, centres on a child—symbolically, of course, but also practically. Our “tiny tots with their eyes all aglow” both inspire us with their hunger for magic and place pressure on us with their insistence on making it happen. Sadly, some of us lack the resources, health, energy, or stability needed to create that magic. Others will see their children only briefly as they navigate shared custody. Some will celebrate Christmas while their children are away, and others carry grief for children lost or never had. And some feel exhausted precisely because they are surrounded by children! So if Christmas feels complicated to you today, perhaps that is what this night invites us to face.

As an infant, the Christ-child certainly complicated the lives of his parents; as an adult, he challenged the leaders of his time; and for two thousand years since, he has made all our lives more difficult by calling us to heed the Beatitudes and love our neighbours. Yet to me, it is not coincidental that a child stands at the centre of a major feast in our Church calendar, because it is from children that I have learned a few essential elements of faith that I would like to share with you this evening.

I should say, though, that the family-oriented spirit of Christmas that we assume to be “traditional” is, in fact, a relatively recent, nineteenth-century development in England. It emerged from the Victorian-era popularity of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol that coincided with the renewed interest in ritual associated with the Anglo-Catholic movement, and an upper-class trend of playing instruments and singing at home for entertainment, à la Jane Austen’s novels. Many beloved carols date from this period, though another Christmas classic, Part I of Messiah, belongs to the eighteenth century. But before that, Christmas had been banned altogether in seventeenth-century England, Scotland, and parts of America, largely in reaction to the revelries of the Tudor period that had preceded it.

What remains constant across time is that all these versions of Christmas have taken place in a world that was neither calm nor bright. A child may be the symbolic focus of Christmas, but a child is also the ultimate image of unfinishedness—a quality that characterizes our world as a whole. That first Christmas itself did not usher in a happy ending to our shared story. “Happy golden days” have never existed, and “peace on earth” seems as utopian a hope now as it did in the days of Caesar Augustus, the first Roman emperor (27 BCE–14 CE). I do not need to rehearse the horrors of our news cycle, but I will note a parallel between the so-called Pax Romana, which Augustus established by ending the turmoil of the Roman Republic and maintained with an iron fist, and contemporary regimes in which stability comes at the cost of democracy. The census that brought Jesus’ family to Bethlehem was one means of exerting imperial control and extracting taxes from an occupied region, and the birth of the promised Prince of Peace did not change that. Perhaps this is why his people so easily handed him over for execution and asked for the release of a violent insurrectionist instead. In other words, the world into which Jesus was born was as unfinished as our own, or as that of eight centuries earlier, when Isaiah spoke of “the land of deep darkness” yet promised that a light would enter it through the birth of a child.

Indeed, God still does—and always has—come into the world through the body of a child, every child, full of promise and potential wrapped in fragility and need, both complicating and saving the world one life at a time. And so, like Mary, every woman experiences the Annunciation as some version of oh no, is this really happening—at the realization of pregnancy and again as labour begins—excited and daunted at the same time. Of Jesus’ own birth, however, we know very little. Only Luke gives us the familiar narrative of the census and the manger, the angels and shepherds. Matthew adds Joseph’s dilemma, the flight into Egypt, the visit of the Magi, and the violence of Herod. With so little detail to go on, we tend either to fill the gaps with Hallmark imagery—the bleak midwinter and glowing snow, the silent night and quiet newborn—or to ask unanswerable questions. What inns existed in first-century Palestine? Who would waste wood in an arid region to build a barn? Does a December birth fit with sheep being out at night? And how does miraculous conception work?

Questions are not antithetical to faith, but some may be more fruitful than others. This is where I turn to children for their wisdom. Children tend to ask out loud what many adults quietly wonder, and instead of fruitlessly challenging the archetypal details of ancient texts, they press into deeper questions. Each of my children has, at some point, posed versions of the questions my youngest has been asking recently: “How do you know that God is real if magic isn’t?” “Why don’t we see miracles today?” “Why did everything big already happen in the Bible?” And always the coup de grâce: “How can I tell if it’s really God talking to me in prayer, or if it’s just my imagination?”

How, then, is theology different from mythology? I believe the answer lies in lived experience. We do not know God in the way we know facts, but through memories of transcendent moments, gathered over time and treasured in our hearts (which is what Mary is said to have done, Luke 2:19). Many people today long for faith but hesitate to admit it, relegating it to childhood. Yet the people who preserved the biblical stories were neither naïve nor unsophisticated. Scripture reflects our longing for encounters with the divine, and the interpretations of such encounters. And so, when I pose my child’s questions back to her, she realizes that what she longs for is already contained within the sacred texts. Which miracle would she choose? “To live forever.” What “big thing” would she want to witness? “For God to show himself as someone we can see.”

I keep telling my children—and our congregation—that yes, Jesus is still being born today, minute by minute, in our thoughts, feelings, and choices. And yes, miracles do happen. Every child conceived is a miracle, since it is never up to us which attempt “works” or what kind of life unfolds. Another miracle is the ability to keep living after loss, even remaining capable of new love. Another is the steady unfolding of scientific insight and discovery. The “big things” continue to happen today just as they do in Scripture—never outside the material world, but through light and cloud, fire and wind, burning bushes and whirlwinds. God speaks through minds and bodies, landscapes and stars, emotion and imagination. “God speaking through our imagination” and “our imagination speaking” overlap, and learning to tell the difference is part of growing in faith, as we discern what draws us toward love, courage, and God, and what pulls us away from them. Lastly, our hope is that when our embodied life comes to its close, our consciousness will not be extinguished, and our spiritual life will indeed go on forever.

These kinds of questions are nothing to be ashamed of. Yet what we often focus on instead is what my eldest asked during one of my first Christmases as a mother. After a long day of trying to make the season magical, I tucked her into bed and she asked, “Why do you say no to everything I ask for? Why can’t I choose something that will always make me happy?” When I asked what that might be, she said, “I don’t know.” That wondering is deeply human. We sense that happiness lies just beyond reach, yet struggle to name it. We equate fulfillment with freedom, and then wonder why God seems always to say no. But this way of wondering can also be unhelpful, because it obscures the many ways God has already said yes—often before we even knew how to ask.

Christmas places at its centre not a plan, not certainty, but a child—utterly helpless and yet full of possibility—and a parent who is called “favoured,” “full of grace,” or “blessed,” not because she has everything she wants, but because she has come to understand her God-given purpose. We do not know how our stories will unfold, only that each of us is entrusted at birth with a purpose of our own. And just as children grow by being held, accompanied, encouraged, and educated, so too the peace Isaiah imagined arrives in community. Our lives in isolation are ordinary, just as Christ’s birth, life, and even death were ordinary. Yet when we come together, our shared life becomes extraordinary—in worship and prayer, in music that rivals the choir of angels, in care for the unwell, in sharing both grief and joy, and in raising children together.

And so, year after year, on Christmas Eve, we do not seek magic. We come instead to “ponder in our hearts” the ancient truths handed down to us. We do not presume that everything is resolved or every answer known, but that God continues to be born into an unfinished world, where relationships are still mending, hearts are still learning to trust, and there is room for questions, for growth, for divine presence, and for the fragile beginnings of love.

Thanks be to God. Merry Christmas.

Leave a Reply to Cynthia Majewski Cancel reply